This will be a brief overview of the proper way to handle a debate.

1.

Format: First, it is important to let everyone know who and what you are addressing. If you are only responding to one person, mark which section you are responding to. This can be done a number of ways — such as an "in regard to..." or a "[topic]:" at the beginning of each new idea. If you are responding to more than one person, clearly identifying whom you are addressing is also helpful. My system is to start with an

underlined name, then write all responses below that. When you are done with the first person, leave a space, then

underline the name of the next person you wish to address. This exact format is not required, but uniformity may help in clarity. It should look something like this:

- Quote :

- strat

religion: blah blah blah

discrimination: blah blah

giant incisors: blah blah blah blah

mbacolas

bigfoot: blah

loch ness monster: blah blah blah blah blah

2.

Sources: Sources are incredibly important for an intellectual conversation; no-one will get anywhere if we cannot agree on the same facts. Some sources are more credible than others, and here are a few things to consider when looking for sources of various types:

News: All news media has bias, some more-so than others. For example, Fox News has a heavy American right bias; MSNBC has a heavy American left bias. This is not to say that these news sources are not credible in any way, but it does mean that having another place say it will be more credible to your opponent. Truthfully, a very good news sources is the BBC. The BBC is known to be the least bias (slightly left leaning) of the news organizations in the UK, and they have a more neutral, outsider's perspective on non-UK events.

Science: The hallmark of a scientific sources is something published in the peer reviewed (PR) literature; however, just because it's been published does not make it true. If you find a PR paper, look at the date. If the paper is 10+ years old, look for another, more recent one that refutes it. Studies do date, so make sure it's the most up-to-date article on the subject. After PR comes large science organizations such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), National Academy of Sciences, International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and so forth. If large bodies such as these agree with a position, it is a very strong voice. Also, the articles published by these sources are good reviews of large bodies of data. Next we have books and science magazines. Both magazines and the authors of books have a reputation to maintain. If National Geographic publishes a bunch of crappy articles, the scientific community will berate them, and they will not do as well on sales; however, magazines and books are primarily there to make money, so things are often distorted or dramatized for the purpose of sales.

Philosophy: Again, the PR literature is an excellent source for papers on philosophy. Two other excellent sources are

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy and

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. There is a PR process that an article must pass to get into either of these encyclopedias. The IEoP is geared more toward an undergraduate understanding of a topic; the SEoP is geared more toward graduate understanding.

Websites: Anything can be posted on a website, so be very careful on which websites you use. One thing to look out for is: who is making the claim? Is it an anonymous poster? Is it a credible organization? Is it a group of people with an obvious bias? Next: are sources cited? If not, why should we believe this website's words? In general, look at the sources provided by a website, and only use the website if you see it conveying the message of the sources in a more coherent fashion than the source material. And remember, if a website's sources is another website, figure out where that website got their information.

Wikipedia: Wikipedia is a mixed bag. It should not be the main source for any scholarly debate; however, going to Wikipedia to familiarize yourself with a topic is not a bad idea. Though it is full of errors, the general overview is usually fairly good. And a good article on Wikipedia will give sources, which you can then follow to learn more about something specific. Some things do not require very strong sources, though, and if you have read a Wikipedia entry, and find it to be credible, then you may use it. But if someone demands more than a Wikipedia page, don't argue, and find another source.

Confirmation Bias: All humans have a tendency to seek out information that supports our current ideas, and to reject information that refutes it. Just keep this in mind when searching for information, lest you find yourself using incredible sources, because it's more convenient for you.

3.

Null Hypothesis & Burden of Proof: These are the types of positions in an argument. What type a side is is based on what the argument is.

Null Hypothesis: This is the "defensive" side. The null hypothesis is the position that would be adopted if all other positions are refuted. It may also be the position of the status quo.

Burden of Proof: This is the "offensive" side. It is making a positive statement for the adoption of a claim.

How they work together: Let's take materialism vs. supernaturalism. A materialist's position is that there is no credible evidence for anything other than the physical world. This position holds the null hypothesis, so no positive claims need be made for the position (but they can be, if the party is interested in doing so). The supernaturalist's position is that there is more than just the natural world. This position holds the burden of proof, and must show that there is positive evidence supporting the position. In the debate, the person holding the burden of proof makes an argument, and then the person holding the null hypothesis must refute that argument. The person holding the null hypothesis has the advantage of not needing to make any positive claims, but a single argument that cannot be countered will result in the refutation of the null hypothesis. The person holding the null hypothesis may use ignorance ("we don't know how that works, yet), but overuse may mean the position is more dogmatic than rational.

There may not always be a null hypothesis: In some arguments, there is no clear null hypothesis. For example, did the universe begin from nothing or from divine intervention? Neither answer would be correct if someone only showed that the opposing side is wrong, so the winner would simply be whoever holds the most credible evidence.

Status Quo Null Hypothesis: Sometimes the status quo is the domain of the null hypothesis. For example, in Global Warming, the status quo and null hypothesis is that the Earth is not warming; thus, the burden of proof rests on proponents of Global Warming to show a positive case — the skeptic need only give accurate retorts.

4.

Logical Fallacies: These are important to know, both because you want to avoid them yourself, but also because you want to call others out when they use them. A logical fallacy is simply when the statement being made has one or more parts where the logic breaks down, so the conclusions made may be wrong. IEoP has an article on the various

logical fallacies, but I'll point to the ones I've most commonly come across that are also not blatantly obvious.

Ad Hoc Rescue: refusing to accept your position is faulty in the face of contrary evidence.

Ad Hominem: attacking the maker of the argument instead of addressing the points made.

Appeal to Authority: this one is tricky, and I suggest reading the synopsis provided.

Appeal to Emotions: using someone's emotions as the crux of your argument.

Appeal to Ignorance: using ignorance as an argument for your position, when your position holds the burden of proof.

Appeal to the People and

Bandwagon: saying that, because it's popular, there must be something right about it.

Avoiding the Issue and

Avoiding the Question: avoiding the subject in an attempt to not show yourself wrong.

Begging the Question: also called "Circular Reasoning"; an argument presupposes its conclusion.

Common Cause: assuming two incidents have the same cause.

Complex Question: a controversial presupposition is made by the how a question is phrased.

Equivocation: switching the meaning of a term in the middle of reasoning.

False Dilemma: also called"False Dichotomy"; assuming too few possible positions.

Genetic: assuming the logic is wrong because of the origin of the idea.

Is-Ought: assuming that the way things are are the way things should be.

Line-Drawing: assuming that possible vagueness means a term or position should not be used.

Naturalistic: there are two interpretations of this, so I will state which one should be used for the forum: the latter one mentioned on the link: assuming that if it occurred in nature some way, then that is the way it should be.

Non Sequitur: the conclusion of an argument doesn't follow from what was said in the argument.

Quoting out of Context: also called "Quote Mining"; taking a piece of what was said out of context.

Red Herring: bringing up an irrelevant point to sidetrack the issue.

Scapegoating: blaming something else (usually already unpopular) for a problem when it has nothing to do with the problem.

Selective Attention: focusing on an unimportant part of the discussion while ignoring others.

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: a prophecy is fulfilled because the announcement of the prophecy causes it to happen. See the article for more details.

Sharpshooter's: making random events appear as evidence for a position.

Slippery Slope: saying that the first step should not be taken because it will lead somewhere bad, but there chance of getting to the bad is of low probability.

Special Pleading: making undue exceptions to a universal claim.

Straw Man: attributing easily refuted points to your opponent, even though they do not hold those positions.

Subjectivist: assuming there is reason to believe an issue is subjective rather than objective.

Suppressed Evidence: purposely leaving out evidence that is vital to the debate — usually done when it would be held against one's claim.

Unfalsifiability: making a statement that is incapable of being falsified.

Wishful Thinking: assuming an outcome because it's more desirable than alternatives.

5.

Making the Argument: Above is what to think about when forming one's thoughts, but now to combine them into a coherent, persuasive form. The best way to learn how to form a strong argument is practice, but here is a skeleton guide to help give ideas.

Length: Know that people don't want to read a lot. Because of this, it is important to balance content, clarity, and length. Short, direct questions and answers are the best in these circumstances. Be aware, though, that others are not mind readers, so they may ask for a more detailed explanation of your logic. It is possible that someone will contend that you are using a non sequitur, even if you think there's a logical flow from point to point. In this case, restate your opinion, but go more in depth — you now have their attention, so you can write more before your opponent will bore with what you have to say.

Structure: If your question or retort is only a few sentences, then get it out quick; however, if you are, for instance, beginning a new topic, and want to write several paragraphs, then structuring it as a short essay is very helpful. First, write a paragraph defining what your position is. This is helpful because it is common to see the same word used in two different ways: you will not have a skeleton of a word's definition to latch onto, and your opponent will bring their own interpretation of the word, if there is no set definition in the beginning. Second, write however many paragraphs you want to defending your position — remember to be concise. It is also convenient to number and/or title your sections. This gives the reader an idea of what the current issue is, as well as makes it easier to address when they give a retort. Last, write an introduction and conclusion. The introduction should give an overview the topic you wish to address, and give a

brief summary of what arguments you have used are (remember to state things in future tense). The conclusion should give a synopsis of what was said in the argument proper. Do not be afraid to sound redundant; you may know what you intend to get across, but the more help you give others, the less mistakes will be made by others during their interpretation. Also, this is a very good place to use the official names of various arguments if you know them (ex: I argued for God's existence using the Kalam Cosmological Argument and Teleological Argument); some members of the debate will be familiar with the arguments already, and seeing that these are being used is helpful in avoiding boredom from having to read something they've already learnt.

Sacred Cows: Sacred cows are topics that are said to be off-limit from scrutiny. If we keep in mind that the purpose of our discussions is to both develop our opinions and exercise our critical thinking, it is of no use to us to hold sacred cows — they only serve to hinder our ability to develop. This

will make you seem harsh at times — many people find it acceptable to hold certain ideas above discourse — but it does serve a valuable purpose.

Getting Emotional: Generally, it's not a good idea to get emotional during an argument. Emotions are usually a sign that someone is striking at a sacred cow, and it is acceptable for someone to push the matter to see if your position is one of dogma, or just heavily justified conviction. Certain topics do require emotion, though, as they are not justifiable through logic and facts alone; however, if someone makes a strong case that a topic can be discussed through logic alone, and you find no problems with their reasoning, emotional arguments should be abandoned.

Sourcing: How much of what you present as fact is somewhat tricky. Technically, every factual statement should be sourced; however, some sources are hard to find summaries of/we only have so much time to spend with research; therefore, it is generally accepted that common knowledge does not need sources. For example, I don't need to source myself when I make the statement that a penny dropped from atop the Empire State Building will fall down. Sometimes there is fuzzy ground on what is common knowledge and what needs sources, and it's better to try to find a source if someone asks for it, rather than try to argue it is common knowledge.

Spelling/Grammar/Definitions: However right or wrong it is, the way you say an argument is important; you sound like you know what you're talking about a lot better if you make statements in a more formal manner. After writing something, go back and check it for grammar and punctuation mistakes. Also, most internet browsers (I use Firefox) have a spell-checker built in; however, they're not perfect; for example, "sequitur" comes up as wrong (also "judgement", even though it's a perfectly legitimate spelling!). Such spellings will have to checked by Googling to see what people generally use for spelling. Finally, if in doubt of the meaning of a word, look it up. Firefox allows you to set one of your quick search engines as Dictionary.com, and I use that all the time.

6.

Positive Claim: The positive claim is a much harder position to hold than someone simply trying to shoot holes in your argument. First, be familiar with the fallacies; you do not want to find yourself spending a long time writing an argument, only to have it shot down by a single phrase. Next, make sure to have strong sources; you are trying to prove your point, so your sources need to be convincing. Finally, try to find holes in your own argument; if you see some, don't ignore them! There are two options when finding flaws within your own position: (1) don't use that particular argument, because you know it doesn't work; and (2) humbly admit that this flaw exists, but show why the flaw is, ultimately, inconsequential.

7.

Rebuttal: The way to attack another's position is just as important as setting up the logic of your own. First, try to break their argument into its parts — it's usually easiest to attack a position if you can find what the core points the argument rests on are. Next, try to find where the opposing position is making a mistake. Below is a list of problems to look for in an argument. It is slightly devious, but leading people into a logical trap can also be an effective strategy. If you are familiar with an argument already, then leading your opponent to the area where their position falls apart is the shortest route to proving your side.

Reductio ad Absurdum: show that the results of what someone is saying winds up with an absurd or contradictory conclusion. Read the "Basic Ideas" for a good synopsis.

Infinite Regress: show that we require an infinite number of things to explain the event. The famous example of an infinite regress is the idea that the world rests on the back of four elephants. When asked what the elephants are standing on, the answer is, "a giant turtle". When asked what the turtle is resting on, the answer is, "another turtle". When asked what that turtle is resting on, the answer is, "a third turtle". And so forth; thus, to justify your position that the earth is held up by four elephants, we need an infinitely high tower of turtles — "turtles all the way down".

Fallacies: calling someone on their fallacies is a fast and efficient way to knock down an argument. If someone has made an ad hominem attack against you, it is better to call them on their fault than try to defend yourself. This goes for all fallacies — there's no point in using reason to argue against a point that's irrational.

Contradictory Evidence: the least powerful, but still useful. If someone makes a factual claim, then bring in sources to show that that claim is wrong.

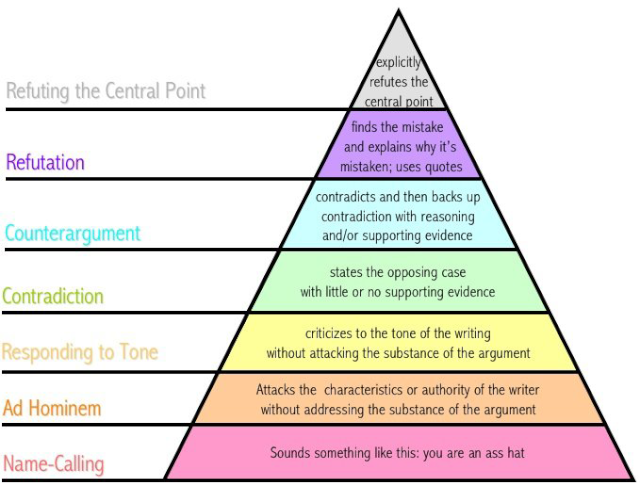

And remember that it's acceptable to admit defeat. This is a good opportunity for a learning experience, but you won't be learning anything if you're unwilling to change your mind. Finally, here is a picture that represents the value of the different types of argument: